Weaving Software into Core Memory by Hand

Watch on YouTube — footage of the core rope weaving process, showing how wires were threaded through and around ferrite cores to physically encode the AGC’s software.

The Apollo Guidance Computer’s software didn’t exist as files on a disk. It existed as copper wire threaded through and around tiny magnetic ferrite cores — core rope memory. A wire passing through a core stored a 1. A wire routed around it stored a 0. Every bit of the flight software was a physical, permanent decision.

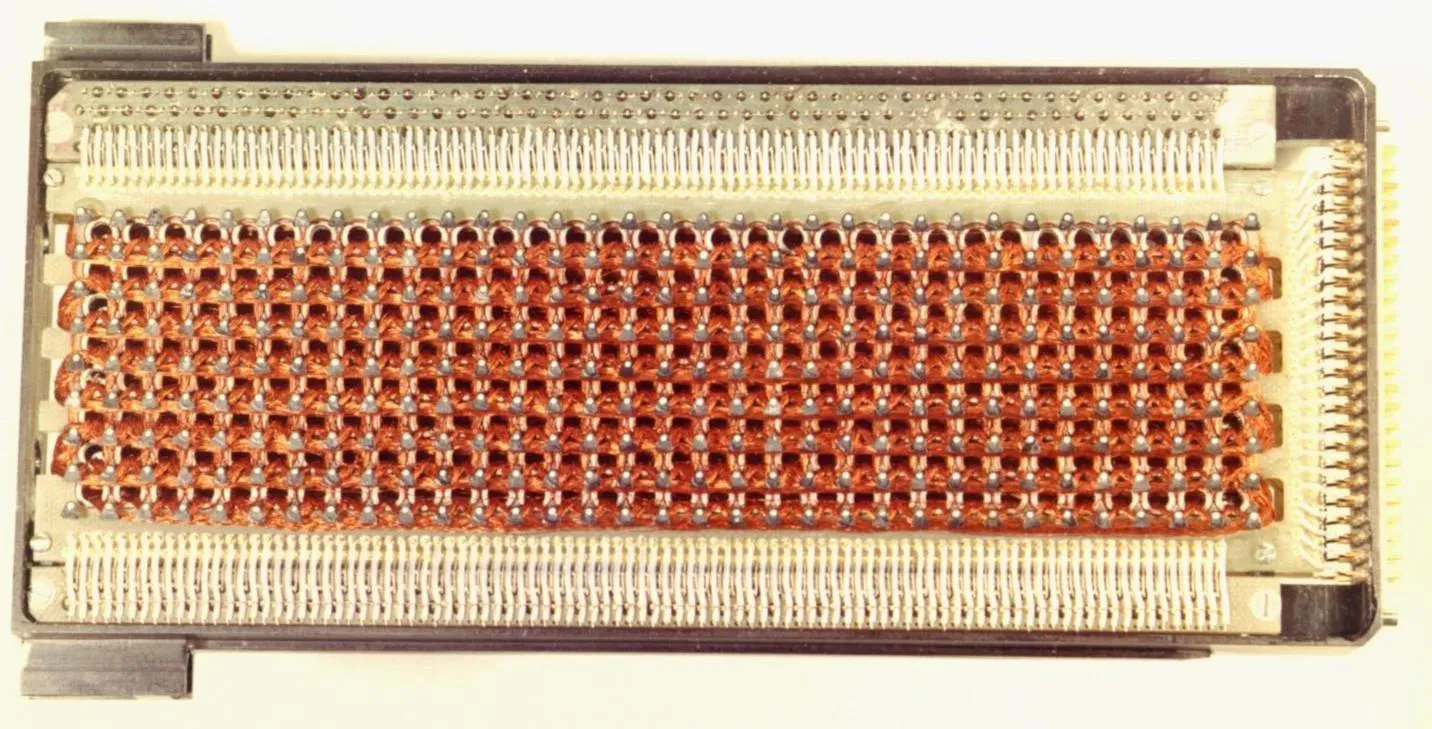

Core rope memory at the bit level. Each ferrite core (copper-colored ring) has wires threaded through it (a 1) or routed around it (a 0). This is what software looked like before there were files. Photo via Ken Shirriff, righto.com.

The numbers are staggering:

There was no undo. There was no patch. If the software changed after the ropes were woven, the ropes had to be rewoven. Code had to be frozen months in advance. This is part of why Hamilton’s insistence on getting the software right before the fact wasn’t just methodology — it was a manufacturing constraint.

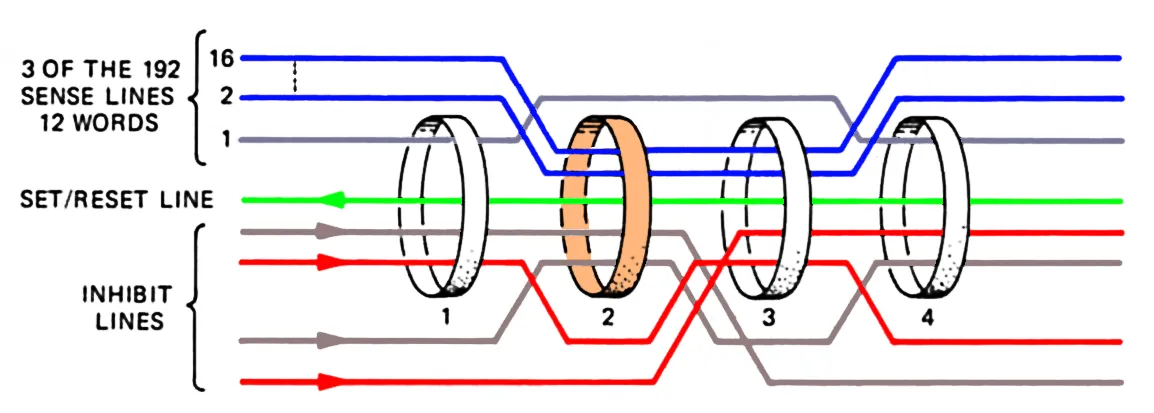

How core rope selection works. Blue sense lines carry the data (through = 1, around = 0). The green set/reset line and red inhibit lines select which core to read. Each core holds 192 bits — 12 words of 16 bits each. Diagram via Ken Shirriff, righto.com.

The core rope modules were manufactured at Raytheon’s plant in Waltham, Massachusetts. The assembly work was done primarily by women — many hired from the local textile industry for their sewing skills, others from the Waltham Watch Company, which had a long tradition of precision handwork. (The same watch company also helped manufacture the high-precision gyroscopes used in the Apollo navigation system.)

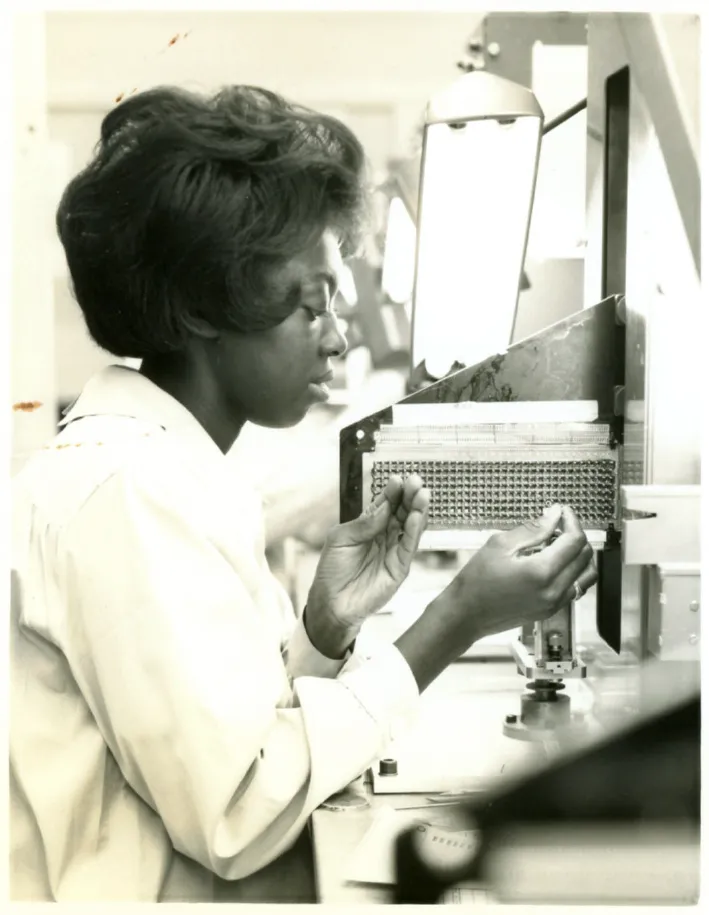

A Raytheon worker threads wire through a core rope memory module at the Waltham plant. The matrix of ferrite cores is visible in the frame she’s holding. Photo via Ken Shirriff, righto.com / Raytheon.

Sitting across from one another at long desks, they passed a hollow needle containing wire back and forth through a matrix of eyelet holes, each holding a magnetic core bead. An automated system — driven by punched tape generated from the AGC’s YUL assembler — read the program and positioned an aperture over the correct core. The weaver threaded the needle through the aperture, installing each wire in the right location. Then the system jogged down to pull the wire around a nylon pin before the next threading.

Two Raytheon workers weaving core rope memory at the Waltham plant, sitting across from each other and passing wire back and forth through the module frame. The rows of ferrite cores are visible between them. The woman on the right wears a Raytheon badge. Photo via Ken Shirriff, righto.com / Raytheon.

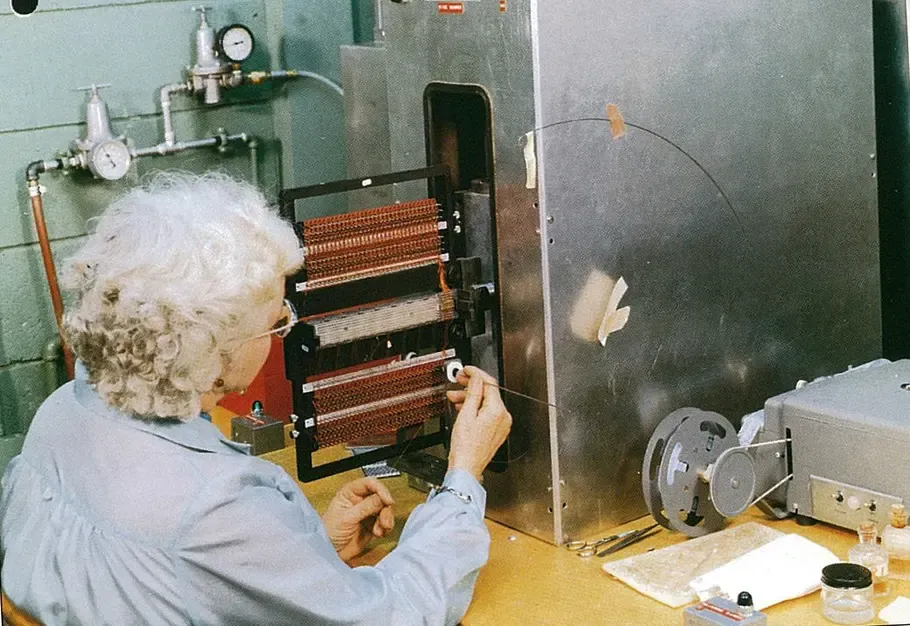

Weaving core rope memory at Raytheon’s Waltham plant. The worker threads a hollow needle through the eyelet matrix while a wire spool (right) feeds the sense line. The metal housing behind the core rack is part of the automated positioning system driven by punched tape. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, image 13006h.

Manufacturing a single rope module took approximately 8 weeks and cost about $15,000 — roughly $130,000 in today’s dollars. 100% accuracy was required. Each component was inspected by three or four people before being stamped off.

The finished product: interior of a core rope memory module. 512 ferrite cores arranged in a matrix, with sense wires woven through them encoding ~6,144 words of flight software. The connector pins along the edges carry signals to the AGC’s sense amplifiers. Photo via Ken Shirriff, righto.com / Computer History Museum.

Most of the women who wove Apollo’s software into hardware remain anonymous. But we know some names, thanks in part to a Raytheon news photograph and a 2019 search by Caroline Kennedy.

A photograph from Raytheon’s records — captioned with their names — shows five women who worked on AGC core rope memory:

In June 2019, on the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, Caroline Kennedy appeared on WCVB-TV Boston asking for the public’s help in finding these five women or their descendants.

Mary Julian’s family responded. Born around 1920, Julian had worked as a seamstress before joining Raytheon. She died in 2004. Her granddaughter Lisa Julian told reporters: “I knew she worked for Raytheon, but I had absolutely no idea that she was part of this.” Her son Jim Julian said: “I knew my mother worked on the Apollo project but never knew what she did. She wouldn’t talk about it. Now here we are, 50 years later… I’m so proud of my mom and what she did.”

Mary Lou Rogers of Waltham worked on a different part of the Apollo production line at Raytheon. In a BBC interview, she recalled the quality control process: “Each piece had to be looked at by three or four people before it was stamped off.”

Mrs. Christina Palcos, a Raytheon worker, suggested the use of laminar workflow benches for the assembly of AGC microcircuits — a practical innovation that prevented contaminants from settling on the work. Her name appears in Raytheon production records.

The term “rope mother” is used in Apollo histories to mean two different things, and most accounts conflate them.

At MIT’s Instrumentation Laboratory, a “rope mother” was a programmer — an engineer responsible for parenting the development of the software for a specific mission. They made sure the code was correct before it was sent to Raytheon for weaving into rope. Rope mothers at MIT were generally male engineers.

The notable exception: Margaret Hamilton was the rope mother for LUMINARY — the Lunar Module flight software that landed on the Moon. As the Smithsonian puts it: “Getting the programs right was the responsibility of Ms. Hamilton, the ‘Rope Mother.’”

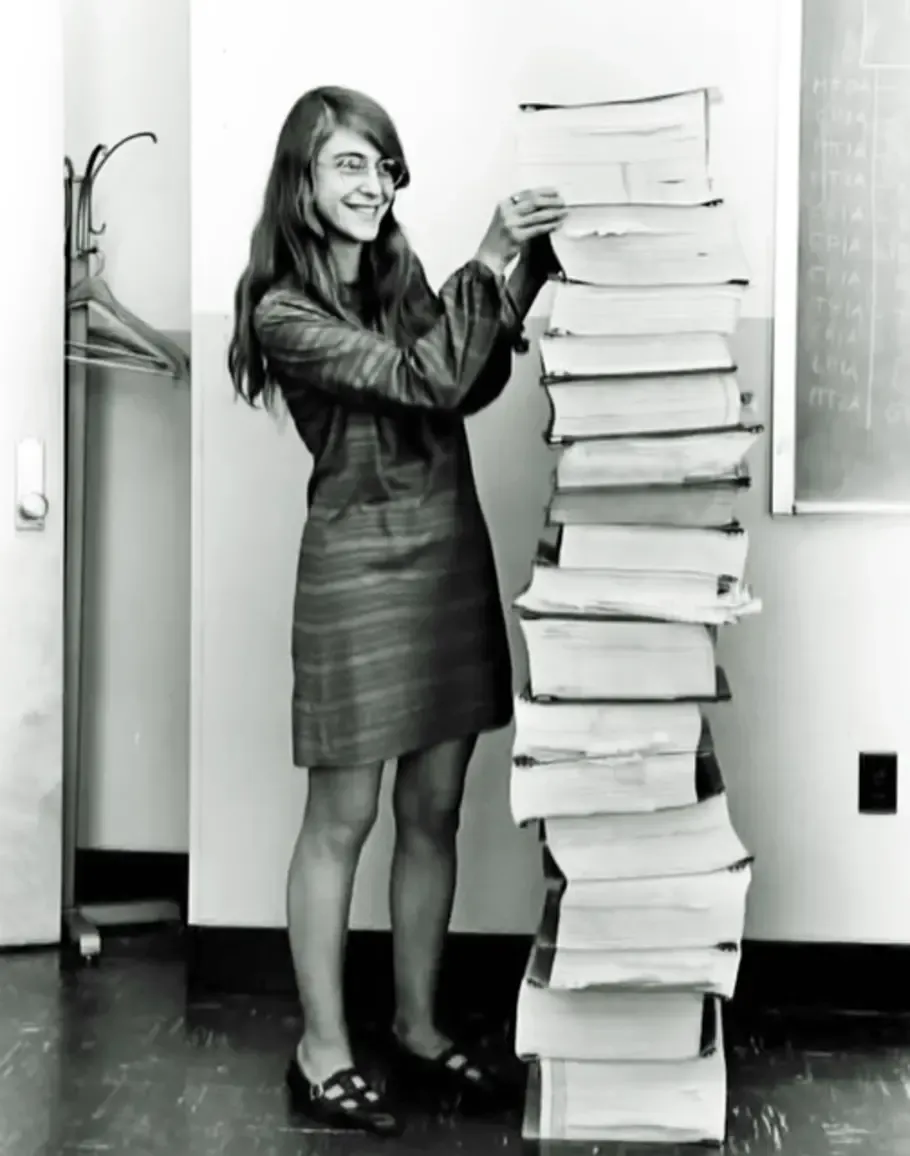

Margaret Hamilton at the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory (formerly MIT Instrumentation Lab) during the Apollo program. The software she wrote here would be translated into wire lists and sent to Raytheon for weaving into rope. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, image 13007h.

At Raytheon’s factory in Waltham, a different group of people — the women on the manufacturing floor — physically wove the ropes. They were not called “rope mothers” in Raytheon’s own documentation. They were called “LOLs” or “space age needleworkers.”

This archive uses the term “rope mothers” for the page title because it has become the popular shorthand for the entire story — the programmers who wrote the software, the women who wove it, and the manufacturing process that turned code into copper. But precision matters: the women at Raytheon and the engineers at MIT did different work, and both deserve recognition on their own terms.

The women at Raytheon represent one end of a sixty-year arc in how humans turn ideas into working systems. Each era brought new tools that changed what “building software” meant — and each time, people worried the craft was dying.

| Era | Medium | The Craft |

|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Copper wire through ferrite cores | Hand-woven at Raytheon from assembler wire lists |

| 1970s | Punch cards and paper tape | Keypunched by operators, batch-submitted to mainframes |

| 1980s | Floppy disks and terminals | Typed into editors, compiled locally |

| 1990s | Hard drives and networks | Written in IDEs, version-controlled, deployed over networks |

| 2000s | Cloud infrastructure | Committed to repositories, built by CI pipelines, deployed globally |

| 2020s | AI-assisted development | Designed by humans, generated and reviewed collaboratively with models |

The medium changed completely. The discipline didn’t. Hamilton’s principles — prevent errors by construction, design the interfaces first, make entire categories of failure impossible — apply whether you’re weaving wire or prompting a model. The question was never how the software gets built. It was always whether the people building it understood what could go wrong and designed against it.

The women at Raytheon knew that every wire they threaded was permanent. That knowledge shaped how carefully they worked. Today, software is infinitely mutable — you can deploy, revert, patch, and redeploy in minutes. The ease of change makes it tempting to be less careful. But the systems we depend on — medical devices, avionics, financial infrastructure — still demand their mindset: do it right, because the consequences of getting it wrong are real.

Margaret Hamilton with the Apollo Guidance Computer program listings. All of this code — every instruction, every constant, every address — was translated into wire lists and woven by hand into core rope memory at Raytheon’s Waltham plant. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, image 12982.

Weaving Software into Core Memory by Hand

Watch on YouTube — footage of the core rope weaving process, showing how wires were threaded through and around ferrite cores to physically encode the AGC’s software.

See how core selection actually works — activate inhibit, set, and reset wires and watch 512 cores respond in real time:

Core Rope Visualizer

Open Core Rope Visualizer — interactive simulation with real wire routing data from MIT Digital Development Memos. Based on Mike Stewart’s visualizer (MIT License).